The season is advancing and fields are starting to go into tillering. I have always been amazed at the capacity of rice plants to adapt to the conditions of the field, producing more tillers in thin stands and less tillers in dense stands. Tillering is one of the important stages that can be most influenced by management practices. Below is a brief review of how the tillering process occurs and its implications for rice management.

Tillering marks the end of the seedling stage. It starts when the fourth true leaf is fully emerged. At this stage, the nodes are all “compressed” close to the ground—the length between nodes (internode length) is less than 0.04 inches. In theory, each node has the capacity to produce a leaf, a tiller and a root; however, tillers and their roots emerge later than leafs. A tiller and its root start growing when the leaf from the third node above is emerging. This means that when the 4th leaf starts emerging (from the 4th node), the 1st node's tiller and root start growing. When the 5th leaf emerges, the 2nd node's tiller and root start growing, and so on.

Tillers emerging in this way from nodes in the main culm are called primary tillers. These emerge all through the vegetative growth phase, but stop when plants reach panicle initiation (the starting point of the reproductive phase). These tillers emerge and branch out from the base of the plant. After panicle initiation, tillers may continue to emerge from preexisting tillers, filling out the space among plants. These tillers are called secondary tillers.

The tillering capacity of rice plants varies with variety, plant spacing, fertility, weed competition and damage from pests. Some varieties are intrinsically better at tillering than others, and these differences can make a variety more “plastic”, adapting better to thin or dense stands. Late maturing varieties have longer periods of tillering than early maturing varieties.

Each tiller has the potential to produce a panicle; however, not all do. Some tillers die before flowering because of shading by other tillers or weeds; the surviving tillers will produce a panicle.

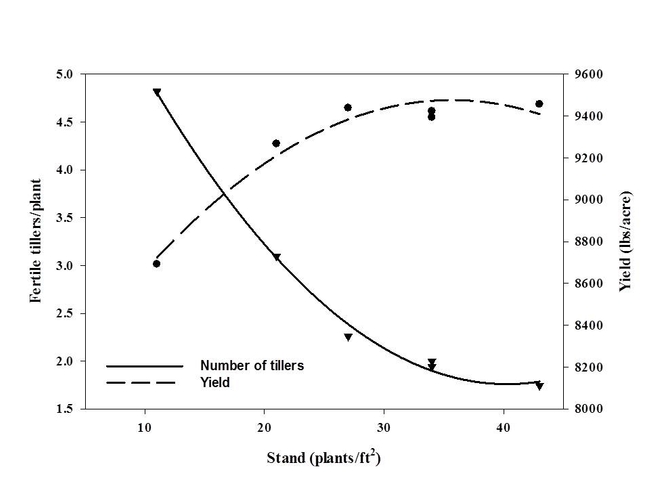

Plants in dense stands produce fewer tillers than plants in thin stands (Fig. 1). In dense stands, the duration of the tillering phase, and in turn, the maturity period for panicles, is reduced. This might be beneficial because it reduces the variability in maturity among panicles. However, if stands are too dense, one runs the risk of disease and lodging. Under low plant densities, more tillers are produced. This can result in a longer period of panicle maturity and a higher number of ineffective tillers (tillers that don't produce a panicle).

Fig. 1. Relationship between plant stand, number of tillers per plant and yield. Butte County, 1984-1985.

Yields under thin or dense stands may not vary much. Because of their tillering capacity, plants can compensate for a thin stand by producing more tillers, and still reach high yields, as shown in Fig. 1. Research in California has shown that to avoid the problems related with thin and dense stands, take full advantage of the tillering capacity of rice plants, and produce good yields, plant densities must be between 15 to 20 seedlings per square foot.